The United States of America is many

things. It is the world's most powerful country, and one of the

largest. It has a history of political revolution and social progress,

as well as a legacy of slavery and genocide. In one sense, mapping the

United States should be a simple matter of displaying borders and

geography. But America is a complex nation with a long and fascinating

history that could never be captured in a single frame. Here's a glance

at America's past and present, in 70 maps.

-

Ecoregions of North America

The vast size and ecological diversity of the North American

continent, the third largest on Earth, has played a central role in

determining how it was settled and developed over millennia. This map

shows how North America's geography, climate, and wildlife have produced

its different ecoregions, coded by color, from the wooded plains of the

Northeast to the enormous semi-arid prairies at the continent's center

to the plateau deserts of the Southwest. So much of America's history

has been about movement — centuries of migration and settlement and,

finally, agglomeration — and geography and ecology have greatly

influenced how that played out.

-

First human migration to the Americas

Humans are relative newcomers to the Americas: the rest of the world

had been settled for tens of thousands of years, perhaps longer, when

the first migrants crossed from Asia into the New World. Many arrived by

walking, very slowly over many generations, up to the northeast extreme

of Asia and then crossing a land bridge, since submerged by ocean, that

reached to Alaska. However, newer research shows that there may have

been a second route: fantastically brave Polynesians who crossed the

South Pacific in canoes, bringing tools, chickens, and certain plants

with them.

-

Economic activity in pre-Columbus North America

The history of North America before European contact is recorded

spottily; if there was an ancient American Marco Polo who traveled

across the continent recording observations about life across societies,

his or her work was lost in the European invasions. But what we do know

still tells an interesting story.

This map, for example, shows the basic economics of pre-Columbus

America. The agricultural communities, in purple, tended to be more

settled and more densely populated, because agriculture requires fixed

infrastructure but can also support more people. Settlement also

requires a certain degree of politics: social hierarchies, divisions of

labor, ownership, and diplomacy between communities. Hunting-based

economies, by contrast, could afford to be more nomadic and informally

organized.

-

The native peoples and languages of North America

North America before Columbus didn't have nation-states of the sort

that we know today (with some possible exceptions, such as the Aztec

Empire), but it did have nations of a sort: peoples who shared common

cultural traits, especially language. This map shows the major language

families and their spread: dark green, for example, shows the

Muskogean-speakers (Chickasaw, Choctaw, and others) clustered in the

Southeast. The Pacific and Gulf coasts are divided by numerous tribes,

each covering small swaths of land, whereas the sprawl of the Central

Plains shows how certain groups came to dominate huge areas.

-

What the US might look like now if Europeans hadn't come

It's impossible to say what North America would look like today if

Columbus had never arrived, but this map of Native American tribal,

cultural, and linguistic areas is a thought-provoking approximation.

Colors represent language groups, whereas lines demarcate the different

tribal groups and their areas of control. What if those groups had had a

chance to form modern nation-states of their own? Had Europeans not

colonized North America, this map and its unfamiliar shapes hint at what

today's sovereign Native American countries and states might look like.

-

European exploration of North America

Christopher Columbus sailed west from Spain in 1492, sponsored by the

Spanish government, which hoped to find an overseas trade route to

southeast Asia. Instead, Columbus landed in the Bahamas, in a part of

the world most Europeans had no idea existed.

This event set off a century-long race among Europe's major powers to

explore and claim the continent (Portugal promised, in a treaty with

Spain, to focus instead on Africa and Asia). This development was purely

about economics, but which explorer happened to land where ultimately

shaped centuries of history: Spanish-explored areas became

Spanish-controlled, whereas French explorers' journeys through the Saint

Lawrence River, Lake Ontario, and the Mississippi River meant that

Quebec and the Mississippi Delta would become French colonial territory.

-

Where place names come from in the Americas

This map breaks out the language of origin for each US or Mexican

state, Canadian province, and Central/South American nation. The East

Coast is dominated by English names, most taken from various British

monarchs (the Carolinas are named in honor of Charles I, Virginia for

Elizabeth I, etc.), cities and regions (York, Hampshire, Jersey), or

other figures (William Penn). Also, unsurprisingly, the West Coast has a

number of Spanish names, and there are a handful of French ones (Maine,

Vermont, Louisiana).

But the plurality of states have names rooted in one or another

American Indian language. The problem is that the states claiming the

names were often nowhere near where the tribes whose words they'd taken

lived. Radical Cartography's Bill Carter

explains,

"Places like 'Mississippi' (Algonquin for 'large river') and 'Wyoming'

(Lenape for a grassy area) were moved thousands of miles by European

settlers."

-

How economics and trade shaped the new world

When Europeans ended 10,000 years of separation between the western

and eastern hemispheres, they did much more than settle and conquer;

they permanently and fundamentally altered the ecosystems of both the

old and new worlds. They brought plants from Europe, Africa, and Asia to

the Americas, such as rice, wheat, and citrus, as well as domesticated

animals such as horses. And they brought American plants back: potatoes,

corn, tomatoes, tobacco, and so on. Known as the Columbian Exchange,

this process transformed agriculture and food, and thus economics and

culture, on both sides of the Atlantic.

-

Immigration from England

The 1607 settlement at Jamestown and the 1620 landing of the

Mayflower were just the initial steps in British colonization of North

America. As this map shows, just as many people came later to Bermuda

and to various Caribbean islands. Indeed, the slave-dependent sugar

industry of Barbados was perhaps more economically important to Britain

than anything in New England. The inset map here also shows the English

origins of places settled in what is now Massachusetts.

-

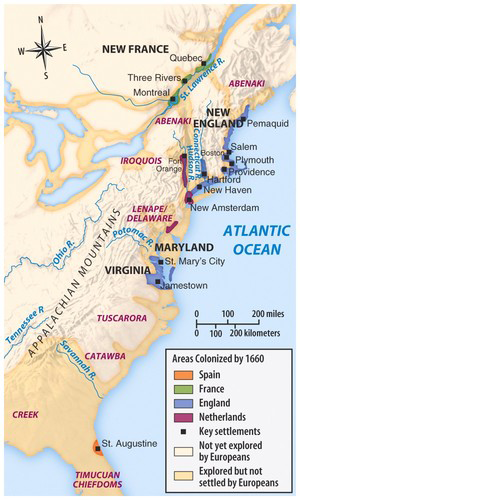

The first European colonies, as of 1660

This map shows the very early stages of European colonization, in the

mid-1600s. Even 170 years after Columbus' arrival, Europeans had

established permanent settlements on very little of North America. Yet

these initial settlements established the contours of later empires and

nations. French colonists encamped along the Saint Lawrence River, a

major trading hub that later became Quebec, and the Spanish had an

outpost in present-day Florida. English and Dutch settlers — the latter

of whom founded New Amsterdam at what is now New York City — established

what would eventually become formal British colonies, and then later

the United States.

-

The political division of North America since 1750

This animated map shows the changes to North America's colonial and

post-colonial borders from 1750 to the present. There are some

interesting nuggets to pull out, such as the tiny transfer of land

between Nebraska and the Dakota Territory in 1882, or the fact that it

took until 1949 for Newfoundland to join Canada. There's also an

interesting

US-Mexico border dispute that was resolved during the Nixon administration.

-

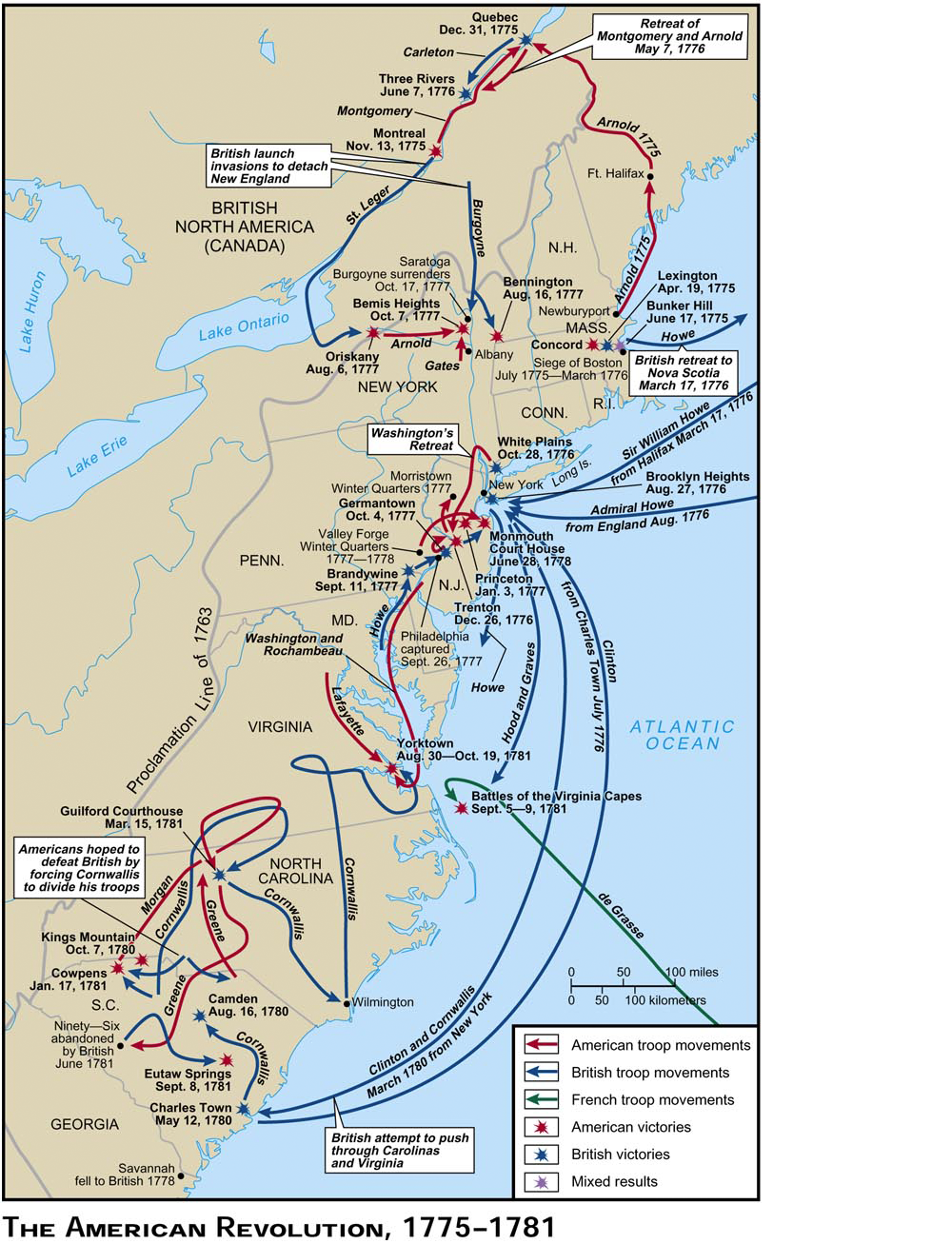

The major Revolutionary War battles

The most salient fact about the Revolutionary War is not that the

colonists won, but that the British Empire, at that point the most

powerful country in the world, lost. That looked, at first, unlikely:

Admiral William Howe, invading from England in 1776, captured New York

City and New Jersey.

But Howe got greedy. Rather than marching north to link up with

British troops coming south from Quebec — the idea was to seal off New

England, then divide and conquer — Howe attacked the rebel capital of

Philadelphia to the south. The British forces, divided, suffered a

humiliating defeat in Saratoga in 1777.

This convinced France, which had been quietly funding the Americans

to weaken the British, that the colonists might actually win. France

declared war against the British in 1778, as did Spain in 1779; the

American colonies were just one front in a global war in which the

British had no allies and several strong enemies. It launched a

last-ditch invasion at Georgia in 1780 but, when that failed, the war

was over.

-

The French and Indian War

In Europe, the Seven Years' War was more or less pointless, with no

side gaining any land at its conclusion. But the territorial

repercussions were much more serious in North America. In the 1763

Treaty of Paris, which concluded the war, France not only lost New

France to Britain — including all of the future US between the

Mississippi and the 13 colonies, as well as all of French Canada — but

also ceded the Louisiana territory to Spain. Napoleon would seize back

Louisiana and sell it to the US in 1803, but New France was lost

forever.

-

Theft of Native Americans' land

This map looks at the conquest of North America from the other

perspective: that of the people being forced off of their land. It

begins by showing Native Americans' land in 1794, demarcated by tribe

and marked in green. In 1795, the US and Spain signed the Treaty of San

Lorenzo, carving up much of the continent between them. What followed

was a century of catastrophes for Native Americans as their land was

taken piece by piece. By the time the US passed the Dawes Act in 1887,

effectively abolishing tribal self-governance and forcing assimilation,

there was very little left.

-

The trans-Atlantic slave trade

About 12.5 million Africans

were sent on slave voyages to the Americas, Europe, or elsewhere in

Africa; due to the horrifically high mortality rates involved, only 10.7

million disembarked. The vast majority landed at sugar plantations in

the Caribbean or Brazil; only about 388,747 disembarked in mainland

North America.

But the United States' slave population grew, unlike those in the

Caribbean and Latin America. "In the antebellum period, US slaves showed

a natural

population growth of some 25 percent per decade,"

according to the University of Liverpool's Michael Tadman. "In sharp

contrast, Caribbean and Brazilian slaves commonly suffered rates of

natural

decrease of 20 percent per decade." The result was an

ever-increasing slave population in the US, magnifying the institution's

importance and the political power of slaveowners.

-

The evolution of slavery in the United States

The fight over slavery in the United States began even before

independence, as constitutional framers clashed over whether or how to

reconcile the world's most barbaric practice with the idealistic new

nation. Though abolitionists lost, states such as Pennsylvania and New

Hampshire ended slavery almost immediately after independence. But the

divide became more than just political, as slavery developed into a sort

of cultural institution upon which southern whites depended for their

economic livelihood and their identity. As America expanded westward,

both pro- and anti-slavery factions tried to claim new territories as

their own. The cultural and political divide deeply polarized the

nation, leading inexorably to war.

-

Concentration of slaves in the US

The

swift growth in the slave population

during the antebellum period helped fuel the institution's spread.

States outside the original colonies — particularly in the Deep South

(Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama) — developed significant slave

industries. Existing slave centers, particularly South Carolina, saw the

practice grow.

This would eventually influence the politics of secession. As Princeton's James McPherson notes in

Battle Cry of Freedom,

slaves constituted 47 percent of the population

in the first states to secede (South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama,

Georgia, Florida, and Texas), where 37 percent of white families owned

slaves. By contrast, slaves were only 24 percent of the population in

the upper South (Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, Virginia,

Missouri) and only 20 percent of white families in those states owned

slaves. The states of the upper South initially declined to secede,

though all but Missouri ultimately joined the Confederacy in the

aftermath of the Battle of Fort Sumter.

-

The crucial 1860 election

US politics in the 1850s were dominated by slavery. The Supreme Court's 1857 Dred Scott

decision, which forced western territories to allow slavery, only

intensified debate over the issue. Members of the new, anti-slavery

Republican Party, such as ex-Rep. Abraham Lincoln, warned that the Court

could force slavery on the North next unless the practice was ended

outright.

In 1860, the Republicans nominated Lincoln for president in a

four-way race. The Democrats split on regional lines, with pro-slavery

Southern Democrats nominating John C. Breckinridge, and

compromise-minded northern Democrats picking Stephen A. Douglas. John

Bell of the Constitutional Union Party, which advocated for the status

quo and against secession, was also a major contender.

Lincoln won with 40 percent of the vote, without carrying a single

southern state. Southerners, feeling they were no longer represented by

the GOP-dominated government and that their way of life was under threat

from Lincoln's abolitionism, almost immediately began to secede. (Note:

South Carolina is grey because its presidential electors were chosen by

state legislators, not popular vote.)

-

When states seceded in the months before the Civil War

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina became the first southern state to secede in reaction to Abraham Lincoln's victory. It was

explicit that Lincoln's anti-slavery views,

and those of many in the North, were the primary motivation for

separation. The declaration of secession stated, "A geographical line

has been drawn across the Union, and all the States north of that line

have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of

the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery."

Before Lincoln's inauguration on March 4, Mississippi, Florida,

Alabama, Georgia, and Texas followed suit. While the "Upper South" had

initially rejected secession, North Carolina, Arkansas, Tennessee, and

Virginia flipped after the Confederate raid on Fort Sumter on April 12.

-

The Civil War

There are, very broadly speaking, two stages you can see in this

time-lapse map of the war. From the war's 1861 start until July 1863, it

was defined by southern Confederate victories that halted Union

invasions designed to end the war by capturing Richmond. Confederate

General Robert E. Lee even invaded the north, threatening mid-Atlantic

cities with the aim of strengthening the northern anti-war movement such

that it might unseat Lincoln in the 1864 election and end the war.

In July 1863, however, two things happened: Lee's northern assault

was defeated at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and Union troops captured a

crucial confederate stronghold at Vicksburg, Mississippi. It was the

turning point in the war, the end of Lee's northern invasion and the

beginning of the Union's divide-and-conquer strategy, which culminated

in General William Sherman's devastating 1864 "march to the sea" across

Georgia.

-

The Anaconda Plan

Winfield Scott was 74 years old and had been in the Army for 53 years

when the Civil War broke out. He was in nowhere near good enough health

to lead an army to battle, and would resign later that year, leaving

George McClellan and then Ulysses S. Grant to lead the Union Army for

the duration of the war. But in May, a little over a month after Fort

Sumter, he devised the plan that would — in very altered form — lead to

victory.

Derided as "the Anaconda Plan" by its opponents, Scott's plan

involved blockading the Confederacy along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts,

and then launching a campaign down the Mississippi River to divide the

South. Sure enough, the North's blockade grew more effective over time

and imposed significant pressure on the South, and Grant's victory in

the Vicksburg campaign secured the Mississippi for the Union and marked a

major turning point in the war. While his strategy proved prescient,

Scott's promise that it would bring about a relatively bloodless end to

the war was sadly not fulfilled.

-

US territorial evolution

European settlers and homesteaders had been moving west from the

Atlantic coasts since first arriving. But shortly after independence,

that expansion grew from piecemeal settlements to national policy.

That policy, however, was not always as coherent and deliberate as

the lore of Manifest Destiny implies. For example, when American agents

traveled to Paris to negotiate the Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon

Bonaparte, they initially sought only New Orleans, then one of the

largest and richest cities in North America, but the cash-strapped

Bonaparte sold half a billion acres to fund his expanding wars in

Europe.

Further expansions came in part due to the collapse of the Spanish

Empire and the efforts of pro-slavery legislators to incorporate new

slaveholding territories.

-

The Trail of Tears

The largest act of ethnic cleansing perpetrated by the United States

government began in 1830, when Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal

Act into law, which gave him the power to negotiate the removal of

Native American tribes in the South to land west of the Mississippi. Of

course, those negotiations were corrupt and rife with coercion. Take,

for example, the removal of the Cherokee, which was conducted via

a treaty never approved by leaders of the Cherokee nation

and resulted in, according to a missionary doctor who accompanied the

Cherokee during removal, about 4,000 deaths, or one fifth of the

Cherokee population. Later scholarship suggested

the numbers could be even higher than that.

-

The Mexican-American War

Upon independence in 1821, Mexico gained vast but largely

unincorporated and uncontrolled Spanish-claimed lands from present-day

Texas to northern California. American settler communities were growing

in those areas; by 1829 they outnumbered Spanish speakers in Mexico's

Texas territory. A minor uprising by those American settlers in 1835

eventually led to a full-fledged war of independence. The settlers won,

establishing the Texas Republic, which they voluntarily merged with the

United States in 1845.

But Mexico and the US still disputed Texas' borders, and President

James K. Polk wanted even more westward land to expand slavery. He also

had designs on Mexico's California territory, already home to a number

of American settlers. War began in 1846 over the disputed Texas

territory, but quickly expanded to much of Mexico. A hardline Mexican

general took power and fought to the bitter end, culminating in the US

invading Mexico City and seizing a third of Mexico's territory,

including what is now California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and

Texas.

-

Settling the West

This is both a map and a chart, each of which demonstrates a crucial

fact about the development of America's immigrant population. The map

makes clear that while the Upper Midwest, the Rocky Mountains region,

and Northeastern cities were major immigrant destinations, immigrants

generally steered clear of the South, which lacked the opportunities for

industrial employment that the rest of the country offered. The chart

shows that this wave of immigration came to a sudden halt in 1914. We

tend to forget this now, but with some exceptions (like the US

anti-Chinese policy)

immigration was fairly open between Western nations before World War I. The outbreak of war ended the open borders era, and while

almost all the nations of Europe maintain open borders with each other, the US remains restrictionist.

-

The mean population center over time

Yes, the 1800s were the age of westward expansion, but the trend

never really stopped. One way the Census Bureau measures geographic

shifts is by measuring the US's "mean center of population" — that is,

"the place where an imaginary, flat, weightless and rigid map of the

United States would balance perfectly" if all Americans weighed exactly

the same. As of 2010, that point was near the village of Plato,

Missouri. But the point's westward and southward trajectory doesn't

necessarily mean that lots of Americans are packing up and moving west

and south, although that was an early trend. Rather, it often means that

the populations of the West and South have grown faster than the

Northeast and Midwest. That includes people moving, but also shifts in

birth rates and immigration. — Danielle Kurtzleben

-

The Dust Bowl

Most of the devastation wrought by the Great Depression doesn't lend

itself easily to maps, but the Dust Bowl does. This map shows changes in

population by county from 1930 to 1940. You'll notice two clear trends:

the Plains states shrank dramatically, while the West Coast grew. The

combination of wind erosion and drought made it nearly impossible for

thousands of families to make a living farming, prompting a mass

migration to California — just like their fictional counterpart,

The Grapes of Wrath's Joad family. According to a 2009 study by Harvard economic historian Richard Hornbeck,

only 14-28 percent of the damage done by the Dust Bowl to farmland values has been reversed since then.

-

Great Migration

The Dust Bowl occurred in between two other transformative

migrations: the first and second Great Migrations, in which millions of

African Americans moved from the South to cities in the North, Midwest,

and West Coast, spurred both by the brutality of Jim Crow and the

southern sharecropping economy and by the economic opportunities offered

by cities like New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, and Los

Angeles. The vast cultural, political, and economic impact of the Great

Migrations is difficult to overstate. "It would transform urban America

and recast the social and political order of every city it touched,"

Isabel Wilkerson writes in

The Warmth of Other Suns,

her masterful history of the migrations. "It would force the South to

search its soul and finally to lay aside a feudal caste system. It grew

out of the unmet promises made after the Civil War and, through the

sheer weight of it, helped push the country toward the civil rights

revolutions of the 1960s."

-

How migration spread the blues

One concrete cultural product of the Great Migration was the

development of northern blues. Blues music originated in the Mississippi

Delta, but was developed significantly by northern performers like

Chicago's Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf, Detroit's John Lee Hooker, and

Los Angeles' T-Bone Walker. And that's just the tip of the iceberg. The

Great Migrations contributed to the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, to

the emergence of New York City's jazz scene, and — principally through

Motown in Detroit — the development of soul.

-

Interstate highway system

This map of the nation's interstates was made in 1957, just a year

after construction of the interstate system was authorized by the

Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956. Initially designed in part to

move military convoys

in case of a foreign invasion (the project was originally named

"Interstate and Defense Highways"), it became a massive infrastructure

project with significant economic and cultural impacts. The highways

increased interstate trade and tourism. They also made long-distance

commuting more viable,

enabling suburbanization — and the cultural homogenization that came with it.

-

Every presidential election since 1856

Since 1856, every American presidential election but one featured the

Democratic and Republican nominees as its top two contenders. (The

exception is 1912, in which Republican incumbent William Taft placed

third after Democrat Woodrow Wilson and Progressive Party candidate

Teddy Roosevelt.)

As this map shows, until very recently Republicans were the party of

the North and Democrats the party of the South. That makes sense:

Republicans were the party of the Union and Reconstruction, whereas

Democrats were avid advocates of slavery and segregation, making the

South a natural power base.

But after Democrats' embrace of civil rights at the 1948 convention,

and especially after Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964,

the parties' power bases began to flip. It was a slow process:

Democrats were winning Tennessee and Louisiana as late as 1996, and

Republicans won Vermont as late as 1988.

-

Sources of immigration over time and largest group per state in 2010

Mexico is, of course, America's largest source of immigrants today.

But as late as 1990, many states still counted Germany as their largest

source. German-Americans have been more or less fully assimilated, and

identification as German-American — rather than just white — is

increasingly rare, but this time-lapse map emphasizes just how recently

first-generation German immigrants were a major demographic group in the

US.

-

American ancestry by county

Here's another way to illustrate the scale of German immigration to

the US. While the data is 15 years old, the basic point conveyed here

— that in the Midwest and Plains, pluralities in most counties claim

German ancestry — stands. The map also serves to illustrate the "Black

Belt," the region of the South with the largest concentration of African

Americans, as well as large Italian- and Irish-American communities in

the Northeast. You can also see the trend in Appalachia and other parts

of the South, where people tend to simply identify their ancestry as

"American."

-

Indigenous population density

This map of indigenous population density today shows the effects not

just of the initial disease-driven depopulation of North America in the

wake of European settlement in the 15th-18th centuries, but the long

effort of the US government in the 19th century to remove Native

Americans from their homes and place them in reservations of its

choosing. The Cherokees of Georgia are gone, having been forced to

relocate to eastern Oklahoma. A handful of counties in the upper Plains

states, Arizona, and New Mexico have large or majority native

populations. Alaska Natives are still a majority in a number of

counties. But in most of the country — especially in the South, Midwest,

and Northeast — Native Americans make up a vanishingly small percentage

of the population.

-

What Americans call their flavored soft drink

Here's an oldie but a goodie. The question of what to call carbonated

soft drinks is surprisingly divisive, with coastal elites picking

"soda," the Heartland opting for "pop," and the former Confederacy

largely standing up for "coke" for maximum confusion.

-

Most popular Christian denomination

It's tempting to look at this chart and divide the US between the

Baptist South, Lutheran Plains, and Mormon Utah-plus-neighbors, with

everything else overwhelmingly Catholic. But that's largely a reflection

of splintering between Protestant sects. Only in counties with black

dots in them is the largest religious group an outright majority, and

while almost all counties in Utah count Mormons as a majority — and many

counties in Kentucky, Texas, and Mississippi do the same for Baptists

— most Catholic counties don't boast Catholic majorities.

-

Latino population in the US today

It's not a huge surprise to see that the US Latino population is

concentrated in the Southwest and California, as well as in southern

Florida and major northern cities like Chicago or New York. But there

are still some surprises — the size of the Latino populations in eastern

Washington state and in southern Idaho, for example. The map also shows

which major cities don't have large Latino populations, like Detroit, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and most of the rest of the Rust Belt.

-

Women's suffrage

This shows the voting rights of women before the 19th Amendment's

ratification in 1920, which effectively ended gender-based restrictions

on voting. Women's right to access the ballot box was guaranteed, at

least de jure. But a number of states had already offered

suffrage to women before the amendment took effect. Many — mostly on the

West Coast but also New York, Michigan, Texas, and some Plains states

— had offered full suffrage, across the board, while others allowed

women to vote in certain elections but not others. But before the 19th

Amendment, eight states didn't give women the right to vote at all. A

constitutional amendment was necessary to give women in those states a

voice.

-

Redlining in Chicago, 1939

The New Deal brought with it a number of government institutions

meant to expand access to housing, including the Federal Housing

Administration (FHA) and Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC). This is

an HOLC map of Chicago from 1939, with neighborhoods color-coded by

stability, as judged by the government.

"On the maps, green areas, rated 'A,' indicated 'in demand'

neighborhoods that, as one appraiser put it, lacked 'a single foreigner

or Negro,'" Ta-Nehisi Coates

explains in the Atlantic.

"These neighborhoods were considered excellent prospects for insurance.

Neighborhoods where black people lived were rated 'D' and were usually

considered ineligible for FHA backing. They were colored in red."

This practice became known as "redlining," and would be the norm in

the housing sector as a whole for decades to come, effectively denying

black people the ability to own homes.

-

Selma march

Anyone who's seen

Selma should recognize this one. This is the

route that Martin Luther King's Southern Christian Leadership

Conference (SCLC), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC),

and the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) took in their march from

Selma, Alabama, to the state capitol of Montgomery in support of voting

rights.

There were three attempts at a march. The first — the "Bloody Sunday"

march — ended with law enforcement officers savagely beating

demonstrators as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge (which you can

see in the top left of the map, by the bend in the Alabama River).

After a second abortive attempt, a federal judge finally granted

SCLC, SNCC, and DCVL the right to march all the way, and President

Lyndon Johnson sent thousands of troops to ensure the marchers made

their way to Montgomery safely. That march ended with King delivering a

speech on the steps of the Alabama state capitol. Within months, Johnson had signed the Voting Rights Act — proposed a little over a week after Bloody Sunday — into law.

-

African-American voter registration in the 1960s

This map not only highlights the locations of major events in the

civil rights struggle of the 1950s and 1960s — the desegregation of

Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, the Freedom Rides of 1961 —

but also shows just how much black-voter registration grew from 1960 to

1971. The effects are dramatic: from 5 percent registration to 55

percent in Mississippi, from 14 percent to 55 percent in Alabama, from

29 percent to 64 percent in Georgia. A lot of that is attributable to

the Voting Rights Act's passage in 1965. Few pieces of legislation in

American history can boast that level of impact, that quickly.

-

Housing in Chicago by race, 2010

Two things stand out in this time-lapse map documenting the racial

composition of Chicago neighborhoods from 1950 to 2010: first, more of

the city became majority nonwhite over that period, and second, the city

didn't get visibly more integrated racially. The former is an old story

by now: in the 1970s, white fear of crime (and, implicitly, black

people) drove whites to the suburbs, leaving the urban core as majority

black and Hispanic. But the stark segregation even in 2010 — there are a

lot of dark blue and red areas, and not a lot of light ones — is

equally striking, and a sobering sign of how far we have yet to come.

-

The student protests

Even by 1960s protest standards, Columbia's

1968 student takeover was intense. Protestors seized buildings and

held the acting dean of Columbia College hostage. People nationwide took notice, and within weeks, prominent activist Tom Hayden was

calling for "two, three, many Columbias."

The Columbia Daily Spectator's

Jerry Avorn and

Jim Dunnigan

made this board game — titled "Up Against the Wall, Motherfucker!"

after the New York-based anarchist group of the same name — based on the

event, with the game board modeled on the school's campus. The

Washington Monthly's Daniel Luzer

quotes

Dunnigan describing the gameplay: "The playing board of Up Against the

Wall Motherfucker! is made up of eleven tracks, each of which represents

a quasi-political subgroup likely to be involved in the spring

demonstration: black students, liberal faculty, alumni, uncommitted

students, and so on."

-

The evolution of marriage equality

The spread of same-sex marriage across the US has been decades in the making. In 1993, a Hawaii judge became the

first to strike down

a law excluding same-sex couples from marriage. A federal ban (the

Defense of Marriage Act) and an anti-marriage amendment to the Hawaii

state constitution followed. A

1999 ruling

in Vermont was the first to actually stick, though Gov. Howard Dean and

the state legislature opted for civil unions rather than full marriage

equality.

Even in 2004, when Massachusetts' high court struck down that state's

ban and San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom began issuing marriage

licenses to same-sex couples, the backlash was strong enough that

11 states passed constitutional amendments banning same-sex marriage.

But after California voters amended their constitution to ban it in

2008, the tide turned, and state after state started repealing their

bans. Today,

37 states have marriage equality (plus select counties in Missouri), and the Supreme Court looks poised to expand that to the whole country.

-

Anand Katakam

Anand Katakam

The Spanish-American War

If there was a single moment when the US became a global power, it

was the war with Spain. The Spanish Empire had been crumbling for a

century, and there was a ferocious debate within the US over whether

America should become an imperial power to replace it. This centered on

Cuba: pro-imperialists wanted to purchase or annex it from Spain

(pre-1861, the plan was to turn it into a new slave state);

anti-imperialists wanted to support Cuban independence. In 1898, Cuban

activists launched a war of independence from Spain, and the US

intervened on their side. When the war ended in Spanish defeat, US

anti-imperialists blocked the US from annexing Cuba, but

pro-imperialists succeeded in placing it under a quasi-imperialist

sphere of influence, seizing three other Spanish possessions: Puerto

Rico, Guam, and the massive Philippines.

-

America as Pacific imperial power

America's brief experiment with overt imperialism came late in the

game, and mostly focused on one of the last parts of the world carved up

by Europe: the Pacific. This began in Hawaii, then an independent

nation. American businessmen seized power in an 1893 coup and asked the

US to annex it. President Cleveland refused to conquer another nation,

but when William McKinley took office he agreed, absorbing Hawaii, the

first of several Pacific acquisitions. Japan soon entered the race for

the Pacific and seized many European-held islands, culminating in this

1939 map, two years before America joined World War II.

-

World War ll

This shows the battle lines of World War II every single day

throughout the war. By the time the US formally entered the war, with

Japan's December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, millions had already died

in Europe and Asia. The war ended with an Allied victory, which marked

the end of a world in which, for centuries, there had been many

competing powers. There were only two global powers left: the US and the

Soviet Union.

-

Korean War

Korea was divided in World War II, when Japan lost control of it to

Soviet and American forces, who occupied the northern and southern

halves, respectively, and installed puppet governments. In 1950, North

Korean leader Kim Il-sung invaded the South, expertly playing Russia and

China off of one another to get their support for a war that neither

wanted. The US and 20 other countries came to the South's defense,

wrongly seeing it as the beginning of a communist plot for world

domination. China wrongly feared it was about to be invaded and sent as

many as a million soldiers into the war. After three devastating years,

both sides reached an armistice, leaving Korea divided and in an

official state of war that remains in place today, and setting up the

world for a half-century of Cold War proxy conflicts.

-

Vietnam War

There were two Vietnam wars. In the first, Vietnamese independence

leaders fought from 1945 to 1954 to expel French imperial rule. They won

and took control of the northern half; the southern half was

temporarily left under the pro-French Vietnamese emperor until elections

could reunify the country. But the US opposed elections, fearing a

pro-Soviet takeover. The Viet Cong, pro-independence guerrillas,

activated throughout the South and in neighboring Laos and Cambodia to

unify the nation by force. The US, again wrongly fearing a monolithic

communist takeover of Asia, sent 2.7 million uniformed Americans, one

third of them drafted, from 1961 to 1975 to fight the Viet Cong. The

tens of thousands of American deaths, the alarming footage of

US-committed atrocities, the American failures against irregular

insurgents, and the sense that the war was meaningless ultimately

transformed not just American politics but much of American society

itself.

-

Cold War alliances in 1980

American and Soviet fears of a global struggle became a

self-fulfilling prophecy: both launched coups, supported rebellions,

backed dictators, and participated in proxy wars in nearly every corner

of the world. By 1971, though, the US and the Soviet Union settled into a

stalemate; Nixon's detente policy accepted the Soviets as something to

be managed, not defeated. This map shows the world as it had been

utterly divided by the stalemate. In 1979, the Soviets invaded

Afghanistan; a year later, Ronald Reagan ran for president, promising to

end detente and defeat the Soviet Union.

-

Afghanistan War

Today's Afghanistan War began in the Cold War: the Soviet Union

invaded in 1979 to defend its puppet government from rebels, who were

later sponsored by the US, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan in an attempt to

bleed the Soviets. When the Soviets withdrew in 1989 and the US

disengaged, the country devolved into civil war between the rebel

factions. In the 1990s, Pakistan helped a new extremist group, the

Taliban, seize control. When the Taliban sheltered al-Qaeda during and

after 9/11, the US and many other countries invaded, and found a mess 20

years in the making. This map conveys the war's post-2001 complexity;

the most important elements may be the Taliban areas, in orange overlay,

and the opium production centers that fund them, in brown circles.

-

Iraq War

A faction of American neoconservatives agitated throughout the 1990s

for an invasion of Iraq, believing that replacing the monstrous Saddam

Hussein with a US-backed democracy would transform the long-troubled

Middle East. Many of those neoconservatives won high positions in George

W. Bush's government. After 9/11, they pushed the CIA for evidence (in

some cases fabricated) that Saddam had backed al-Qaeda and/or was

developing weapons of mass destruction. In 2003, the world largely

refused to sign on to the US-led war. The mostly American and British

invasion was a huge success, overrunning Iraq in only a month. But the

US had not planned for the occupation or reconstruction, and the country

quickly collapsed into bloody sectarian civil war and multiple anti-US

insurgencies. Overwhelming US force finally paused the civil war by

2008, but in 2013 and 2014 the country collapsed back into war.

-

The nuclear powers of the world

In the glory years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, America

became the sole global superpower, unprecedented in world history.

That's still true today, but less so, and this map of nuclear powers and

military treaties is an imperfect but useful proxy for how the world is

slowly re-dividing itself. In brown are the countries under the

American (or NATO) "nuclear umbrella," which means the US has pledged to

protect them with nuclear weapons. Russia has formed its own such

network, in blue. While Russia is much weaker than it was, it still

possesses one of the world's largest militaries and the largest nuclear

arsenal, and is aggressively positioning itself as a hostile competitor

to the Western system. At the same time, the countries in grey —

nuclear-armed nations in neither camp — are fiercely independent from

either the American- or Russian-led orders.

-

Global defense budgets

Another way to show America's status as the sole global superpower is

its military budget: larger than the next 12 largest military budgets

on Earth, combined. That's partly a legacy of the Cold War, but it's

also a reflection of the role the US has taken on as the guarantor of

global security and the international order. For example, since 1979,

the US has made it official military policy to protect oil shipments out

of the Persian Gulf — something from which the whole world benefits. At

the same time, other powers are rapidly growing their militaries. China

and Russia in particular are rapidly modernizing and expanding their

armed forces, implicitly challenging global American dominance and the

US-led order.

-

Gun violence

America's firearm-homicide rate

far exceeds

that of most developed countries, and as this map from the Martin

Prosperity Institute's Zara Matheson shows — using data from the CDC and

the Guardian — many of our cities have rates closer to those of

developing or middle-income countries than to those of Western Europe.

Incredibly, the cities with the highest rates — Baltimore, Detroit, and,

especially, New Orleans — face rates similar to those in Central

America, the homicide capital of the world at the moment.

-

More than half of America's wealth is inside this circle

The northeast corridor — encompassing the 500-odd-mile stretch from

Boston to DC, along with the rest of New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware,

New Jersey, and much of New England and Virginia — accounts for 50

percent of individuals' wealth in the United States. And it's no wonder,

either; despite making up a relatively small share of the US

population, this stretch contains the New York, DC, Boston, and Hartford

Metropolitan Statistical Areas, all of which are among the 10 highest

earning MSAs in the entire country. More income means more assets and

less debt, naturally, accounting for the remarkable fact showcased in

this chart.

-

Unemployment rates by county

Talking about the United States economy as a whole can sometimes

obscure the vast differences in economic well-being that exist between

and within states. Take unemployment, for instance. In much of the

Plains — as well as central Vermont and Grafton County, New Hampshire,

and parts of Oklahoma and Texas near the Plains — there isn't much of an

unemployment problem to speak of, with the rate below 3.9 percent. But

other pockets face unemployment in excess of 14 percent, a mark the US

as a whole never exceeded even in the worst of the Recession. In Yuma

County, Arizona, the rate was a staggering 30.2 percent from October

2013 to November 2014.

-

If the states were equal in population

One consequence of the Senate's design is that the voters of Wyoming get

66 times

the influence as do the voters of California when it comes to Senate

representation. Urban planner and illustrator Neil Freeman illustrated a

creative way to deal with that problem: divvy up the country into 50

new states of equal population. The resulting map isn't just interesting

as a political document; it's a beautiful illustration of how densely —

and sparsely — populated much of the country is. The massive state of

Shiprock — including Las Vegas, Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and Amarillo —

has as many people as the state of Los Angeles.

-

Chance of poor kids escaping poverty

For some people, the American dream — the promise that working hard

will earn you a better life — is alive and well; immigrants to the US

often find their incomes

multiplied many times over

upon arrival. But for people born in the US, prospects are more dire.

This map shows estimates from the Harvard Equality of Opportunity

Project, spearheaded by economist Raj Chetty, which sought to estimate

economic mobility at the county level. It found that in only a

smattering of counties, mostly in the Plains, did children born into the

bottom 20 percent of the income distribution have a decent shot of

making it into the top 20 percent. In the South and Midwest, the odds

are perilously close to zero.

-

High school grads by county

About

86 percent

of Americans aged 25 or older have a high school degree or equivalent.

But the rates vary dramatically depending on what region you're looking

at. In much of the South, pockets in the West, and basically all of

Puerto Rico, high school completion rates are much lower. At a time in

which

demand for more educated workers is starting to outstrip supply, that's concerning. Also note that maps like this can conceal inequalities lurking within individual counties. DC has a

higher high school completion rate than the US as a whole, but big gaps in educational attainment between rich and poor neighborhoods persist.

-

States labeled by GDP-equivalent countries

The US is so rich that it can be hard to wrap your mind around how

much larger our GDP is than any other country's. So Mark Perry of the

University of Michigan-Flint made this map to help out. One important

thing to keep in mind here is that in many if not most cases, the

country being matched to each state has a larger population. California

has 38 million people to Italy's 60 million, meaning it's significantly

better off in per-person terms. There are a few exceptions to this rule,

however; Sweden is less populous than Ohio, and Finland is less

populous than Missouri, which means good things for Scandinavia and bad

for the Midwest.

-

Female life expectancy

The inequality conversation in the US tends to focus on income or

wealth, but health inequalities can be just as concerning, and there's

really staggering inequality in life expectancy across the US. In Marin

County, California — the longest-living county for women — life

expectancy is 85.02 years; the wealthy DC suburbs of Montgomery County,

Maryland, are a close second. By contrast, women in Perry County,

Kentucky, have a life expectancy of 72.65 years, a difference of more

than 12 years from Marin. Put another way: female life expectancy in

Marin County is about the same as that in Hong Kong, while

female life expectancy in Perry County is about the same as that in Bangladesh.

-

Political polarization is worse than ever

In 1994, 2004, and 2014, the Pew Research Center asked Americans 10

questions about their political beliefs, ranging from gay rights to

environmental protection to defense to the economy. They then measured

how likely people were to be consistently liberal, consistently

conservative, or somewhere in between (which could mean they're

moderate, or have strong liberal views on some things and strong

conservative ones on others). They've found that over the past 20 years,

the share of Americans expressing ideologically consistent viewpoints

has grown. It's common knowledge at this point that politicians have

been polarizing ideologically, but Pew demonstrates that regular

Americans are, too.

-

Obesity over time

This map highlights the rapid increase in obesity rates from the

1980s to the present, as well as the disparate geographic impact the

rise has had. Rates in the Deep South and Appalachia are notably higher

than in the rest of the country. But every part of the country has seen

an increase. In 1994, the first year for which we had data for every

state, every one had an obesity rate between 10-19 percent. By 2010,

every state had a rate over 20 percent, and the

trend continues.

-

Shale plays

This map highlights areas in the US where shale gas and oil

exploration is currently ongoing. The most famous are in the Marcellus

Shale (upstate New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio) and the

Bakken Formation (North Dakota and Montana), and while those are the

largest sources, there are plenty more basins across the country. This

shows the remarkable growth of US energy production, driven in part by

shale, which has changed the energy trade not just domestically but

globally.

-

Bakken shale formation

The Marcellus Shale is the most significant shale source of natural

gas, but the Bakken is almost certainly the most significant shale

source of oil. This map visualizes the explosion in oil production in

the late 2000s, which has had huge repercussions for the region. A

one-bedroom in Williston, North Dakota, will run you

$2,394 a month on average, compared to $1,504 in New York City. The fact that workers flocking to the area are overwhelmingly male has had

profound and at times concerning implications for women in the area.

-

School segregation

The demographics of America's public schools are changing. This year, for the first time in American history,

nonwhite students outnumber white ones.

But racial segregation in schooling — driven in large part by

segregation in housing, and thus in school-district placement

— persists. The

vast majority

of white students attend majority-white schools. Black and Latino

students are also likely to be in schools that are majority nonwhite,

except in heavily white rural areas.

-

Happiness

This map

shows

the metropolitan areas in the United States with above average and

below average levels of self-reported life satisfaction, based on CDC

data analyzed by Harvard's Ed Glaeser and Oren Ziv and University of

British Columbia's Joshua Gottlieb. This chart controls for demographic

facts about the areas in question but not income; since income depends

in large part on where you live (and may depend on your happiness level)

controlling for it in this context might be more trouble than it's

worth. "The map shows a band of less happy areas in parts of the Midwest

and the Appalachian states, stretching from Missouri in the West and

Alabama in the South well into Pennsylvania and even New Jersey in the

East," the authors write. "New York City, Detroit, and much of

California also have lower SWB [subjective well-being] than the happiest

areas, which are concentrated in the West, Upper Midwest, and rural

areas in the South."

-

Cost of living

The feeling that everything is more expensive in New York City isn't an illusion. There's

considerable variation

between states and metropolitan areas in terms of cost of living. This

map takes price comparisons for metropolitan areas and then adds in

state-level numbers for counties not in a metropolitan area. As you'd

expect, dense urban areas are significantly more expensive, and rural

areas in the Plains, Midwest, and South significantly less expensive.

There are some conceptual difficulties here: living in Manhattan is more

expensive than living in Indiana, yes, but part of that is because

there are intangible benefits to living in Manhattan that are hard to

model. But overall it's an illuminating comparison.

-

Wealth inequality

Economic inequality is on the rise, not just in incomes but in

wealth, which arguably matters more for political power and long-term privilege. Thomas Piketty, of course, has

argued

that such a rise is inevitable in rich countries. But it's worth noting

just how concentrated a phenomenon the rise in wealth inequality is, as

recent work

by frequent Piketty coauthors Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman shows.

The share of wealth going to people in the top 1 percent but not the top

0.1 percent did not grow

at all over the last 100 years. The entire increase is explained by the top 0.1 percent, and especially the top 0.01 percent.